Outperforming Industry Standard CRDT Implementations

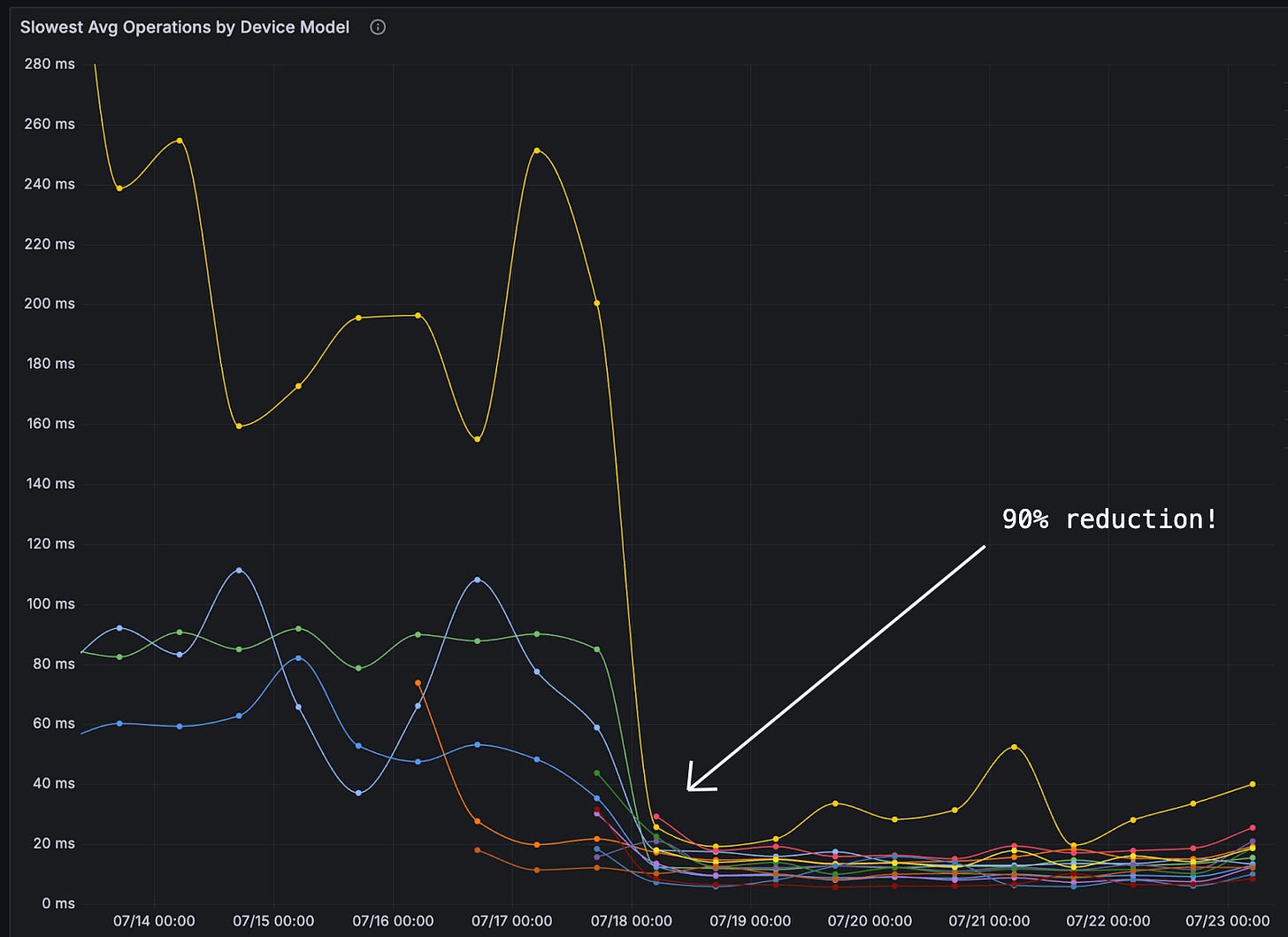

90% less latency and 4x less memory overhead than when we used Ditto

Written by Roberto Perez, Adam Share, and Michael Olson, engineers who helped build Otter POS.

When we set out to sync state across 10+ devices per restaurant without a leader, we started where most teams do: off-the-shelf conflict-free replicated data type (CRDT) libraries. They seemed to work as advertised, but then we measured performance on the low-end Android tablets our customers actually use and we were shocked: database operations were too slow, memory overhead was too high, and device performance tanked.

So we went back to first principles and built something different. By rethinking how version metadata relates to business data, we achieved a 90% reduction in database latency and 4x less memory overhead compared to the container-based approach that dominates the CRDT landscape.

This post walks through the CRDT architecture that most off-the-shelf libraries use, where it breaks down for structured data, and the insight that lets us dramatically outperform it. If you’re syncing protobuf messages between distributed nodes, this approach may work for you too.

Why CRDTs?

A burger joint cannot stop selling burgers just because the internet goes down. The countertop point-of-sale, the kitchen display system, the self-ordering kiosk at the front–all of these devices need to be in sync, regardless of network connectivity. Requiring backend server coordination is not an option. We evaluated other approaches:

On-prem server: Additional hardware at each location creates a single point of failure and operational complexity that doesn’t scale.

Primary device coordination: Restaurant environments are hostile: devices drop from WiFi constantly, tablets overheat, someone spills liquid near a power supply. When your coordinator goes down during the dinner rush, everything stops.

Consensus algorithms (Raft, Paxos): Many restaurants run 2-3 devices. Two devices are clearly unworkable for quorum-based algorithms.

With CRDTs, we remove the need for coordination by embracing concurrent updates across replicas, leaning on an algorithm that deterministically resolves inconsistencies. Devices can update their local state independently, regardless of connectivity status, and then synchronize their data when they reconnect. There’s no single source of truth, no single point of failure, and data in the mesh is guaranteed to eventually converge.

The Standard Approach: Container-Based CRDTs

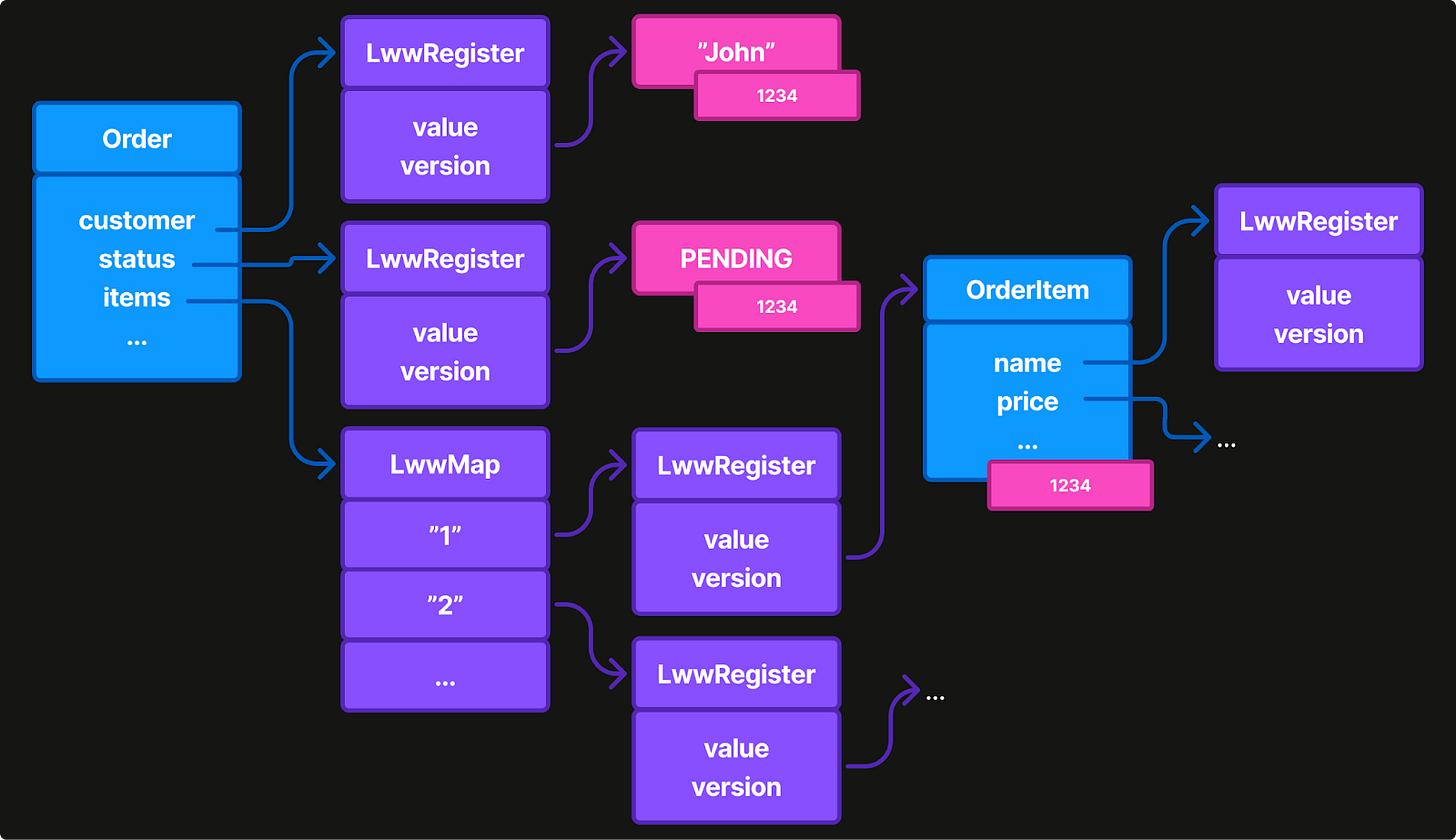

Most CRDT libraries follow a common architectural pattern: wrap every value in a container that implements a commutative, associative, and idempotent “merge” function.

For “last-write-wins” (LWW) data types, this means wrapping both the data and its version metadata in each container. This is the approach used by Ditto, Automerge, Y-CRDT, and most open-source implementations.

// The standard approach: wrap every value in a ‘mergeable’ data type

interface Mergeable {

/** Deterministically merges a remote state with this one. */

fun merge(remote: Mergeable): MergeResult

}

enum class MergeResult {

OURS, // Our data was unchanged (all remote data was ignored)

THEIRS, // The new data is now equal to the remote data

NEW, // The new data is not equal to ours or remote.

}

class LWWRegister<T>(

val value: T,

val version: Long

) : Mergeable

class LWWMap<K, V>(

val entries: Map<K, LWWRegister<V>>

): MutableMap<K, V>, Mergeable

// Your data becomes deeply nested containers

class Order(

val customerId: LWWRegister<String>,

val status: LWWRegister<OrderStatus>,

val items: LWWMap<String, OrderItem>,

// ... every field wrapped

) : MergeableThis pattern is conceptually elegant, each value carries its own merge logic. But elegance doesn’t always equate to performance.

The Hidden Costs

When we deployed a container-based CRDT solution in production, the costs became clear.

Memory explosion: A 1KB protobuf blob became 4-5KB with containers. Each field needed a wrapper with type metadata, value container, and version info, even if they were identical across multiple fields. Average orders were 4-5KB, but complex orders reached 100KB before applying CRDT metadata leading to memory spikes on low-end devices.

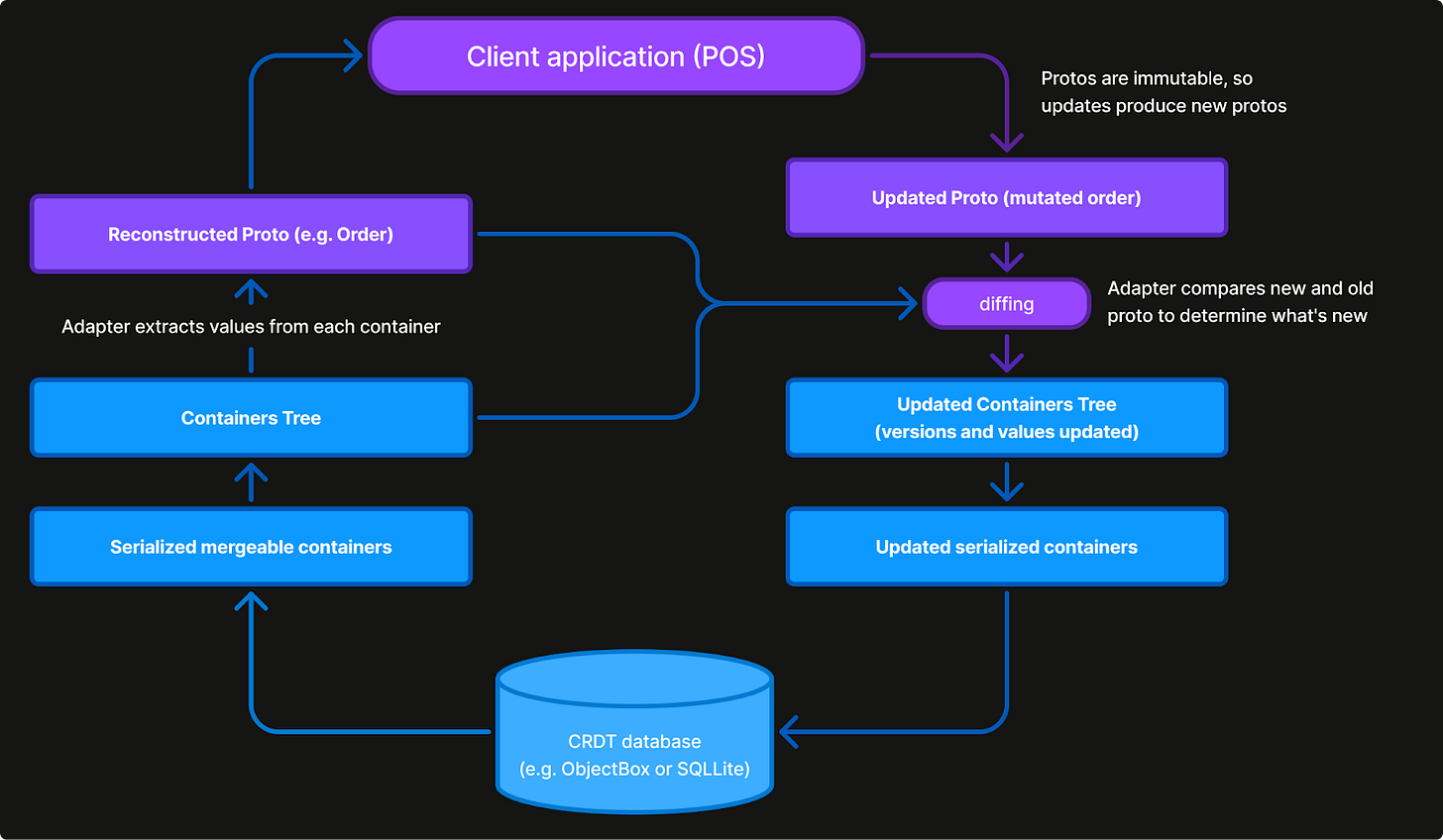

Mapping overhead: For type safety and interoperability with other systems, our data models are defined using Protocol Buffers. This allows us to interact with the data in a natural way, provides clear schema update rules, and enables the reuse of several pieces of infrastructure already available around this technology.

However, this choice also means that we had to implement adapters to map domain object fields into generic container types. As a result, every read and write operation to the database required an O(F x D) transformation (where F is the number of fields and D is the depth).

Version redundancy: When an actor updates multiple related fields, they share the same version. Yet container-based systems store identical version info for each field.

For applications syncing small documents or text, these costs are acceptable. But our devices aren’t just syncing—they’re simultaneously generating bitmaps for receipt printing, fetching menus, processing payments, and rendering content across multiple screens. The CRDT layer competes for limited CPU and memory with everything else.

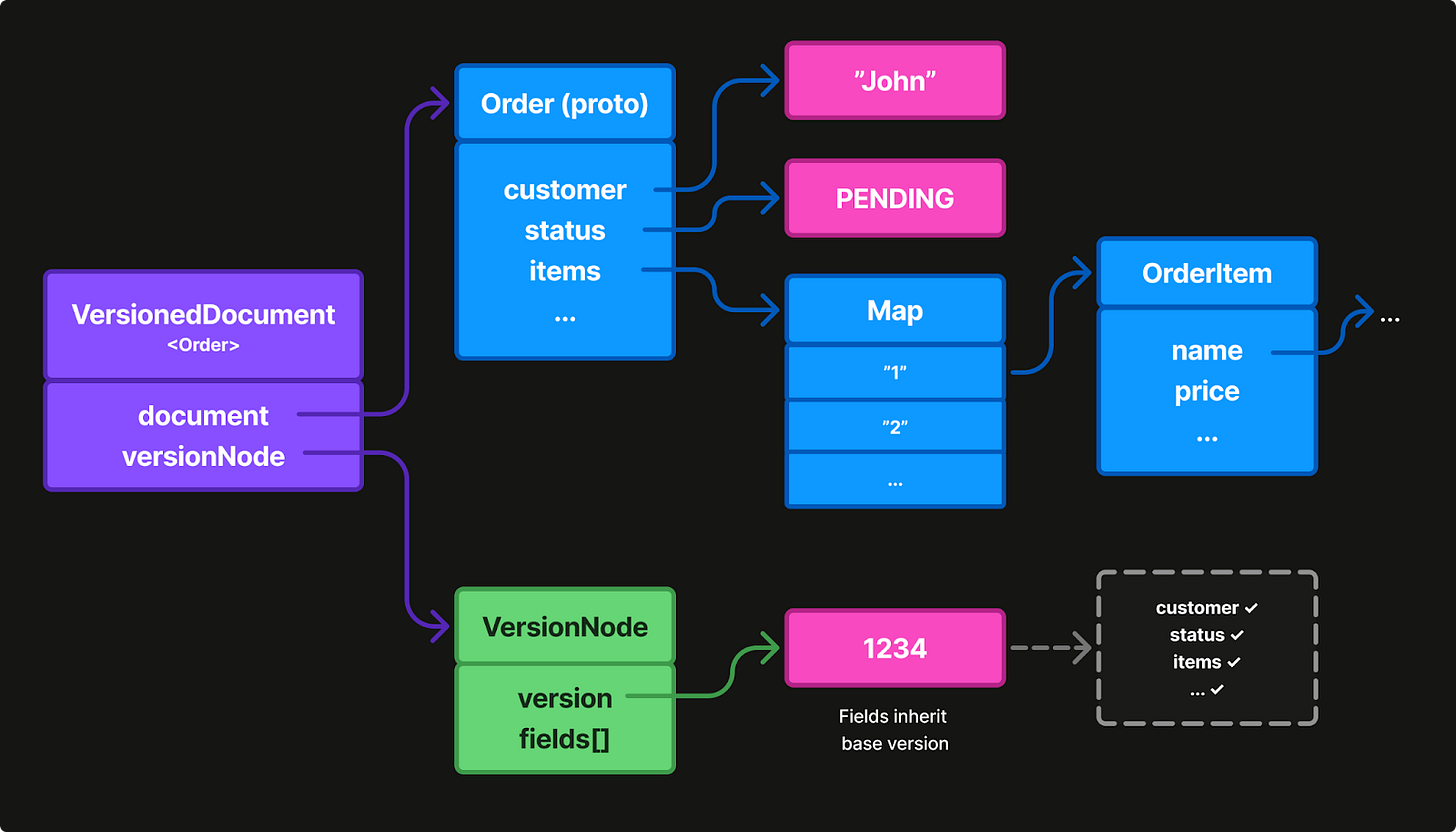

Our Approach: Separate Version from Data

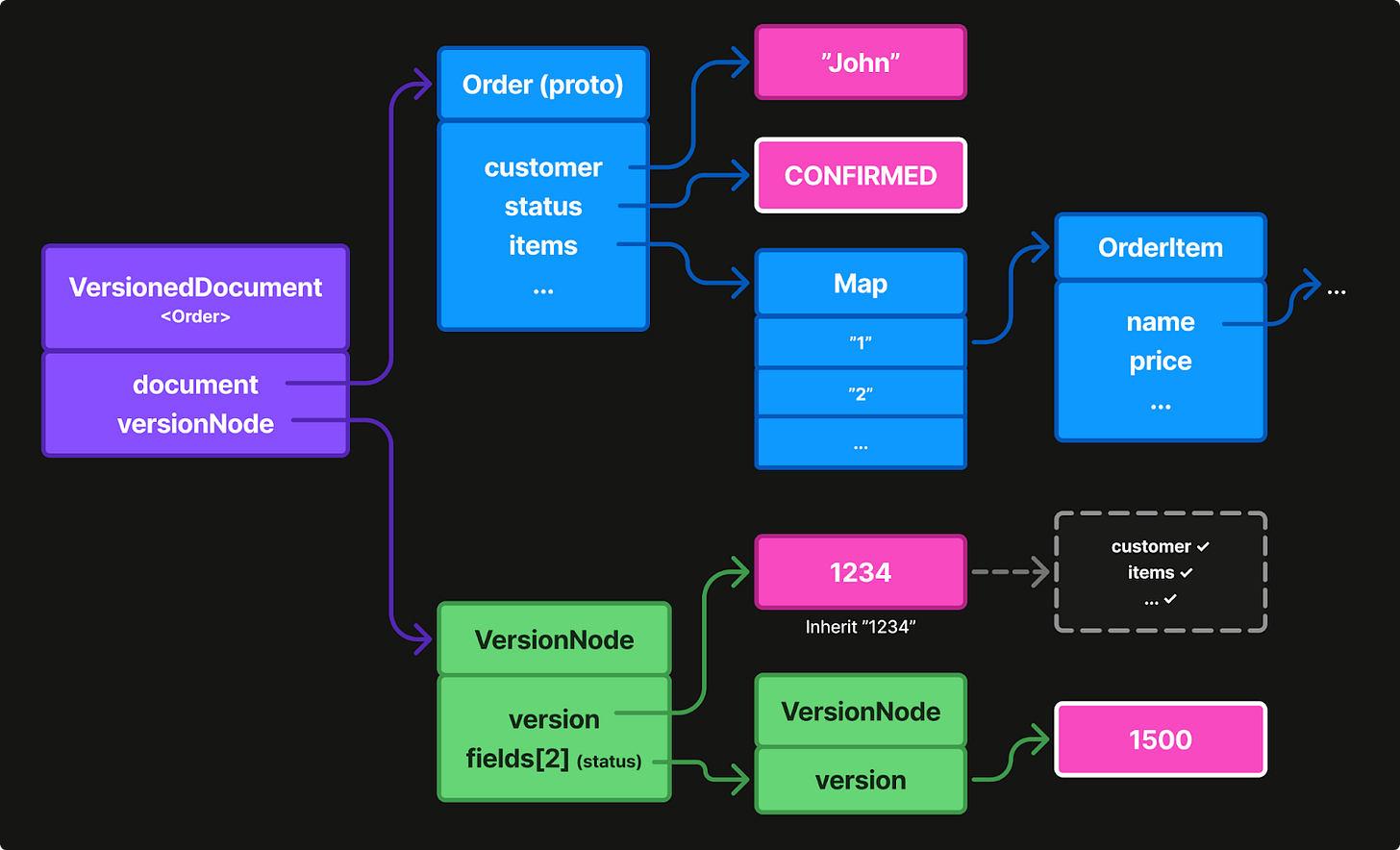

Traditional CRDT libraries embed versions within values. Our key insight: separate them instead. Maintain a parallel version tree that mirrors your data structure. Remove redundant nodes in the version tree by only storing entries for fields that differ from the base version.

For example, in Figure 4 all fields were set at once, so they inherit the root version. No per-field version storage needed.

When a device updates only the status field, then only that field gets a version entry. The other fields continue inheriting from the base version. This gives us O(m) space complexity where m = modified fields, instead of O(F) for all fields.

The data layer remains a clean protobuf domain object, free of any version semantics. The parallel version layer mirrors the data layer, tracking field-level modifications in a sparse tree. Fields without explicit entries inherit the base version from their parent node, providing massive memory savings for typical usage patterns like data that has many fields but only a few change over time.

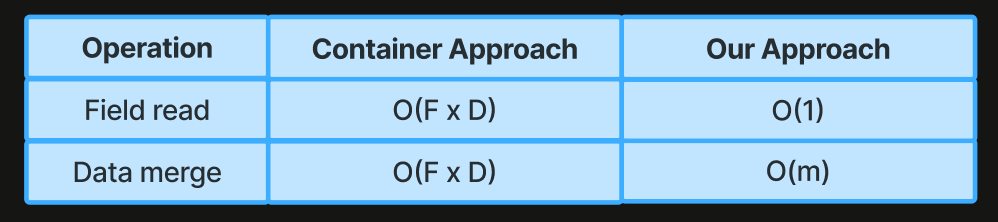

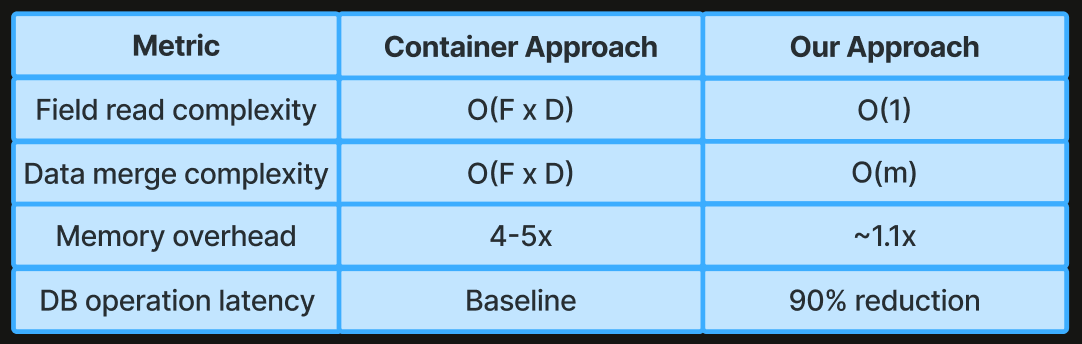

Complexity Comparison

With the container approach you must wrap each field of your data type in the CRDT container wrappers when you merge data types or read the value of a given field, incurring an operational complexity proportional to the number of fields times the depth of your structure.

In our approach, because version metadata is sparse and stored separately from the business data, reads are constant and merging is proportional only to the number of modified fields.

How It Works

Let’s walk through concrete examples using a restaurant order schema. First, the protobuf definition with CRDT options:

import "com/css/protobuf/crdt/data/options/message_options.proto";

import "com/css/protobuf/crdt/data/options/field_options.proto";

message Order {

string id = 1;

string customer_name = 2;

OrderStatus status = 3;

// Nested message: field-level merge by default

PaymentInfo payment = 4;

// Nested message with atomic replacement

Receipt receipt = 5 [

(com.css.protobuf.crdt.data.options.crdt_merge_strategy) = REPLACE

];

// Map: per-key versioning with tombstone TTL

map<string, string> metadata = 6 [

(com.css.protobuf.crdt.data.options.crdt_tombstone_ttl) = 3600

];

// Repeated with ID field: element-level merge

repeated LineItem items = 7 [

(com.css.protobuf.crdt.data.options.crdt_id_field) = 1

];

// Counter: concurrent increments merge correctly

int64 modification_count = 8 [

(com.css.protobuf.crdt.data.options.crdt_merge_strategy) = COUNTER

];

}Last-write-wins doesn’t work for every data type. We still need to support custom per-field merge strategies. We leaned into a schema-driven approach using protobuf options. We’ll go through the default merge case, as well as some of the custom scenarios below.

Scenario 1: Basic Field Merge

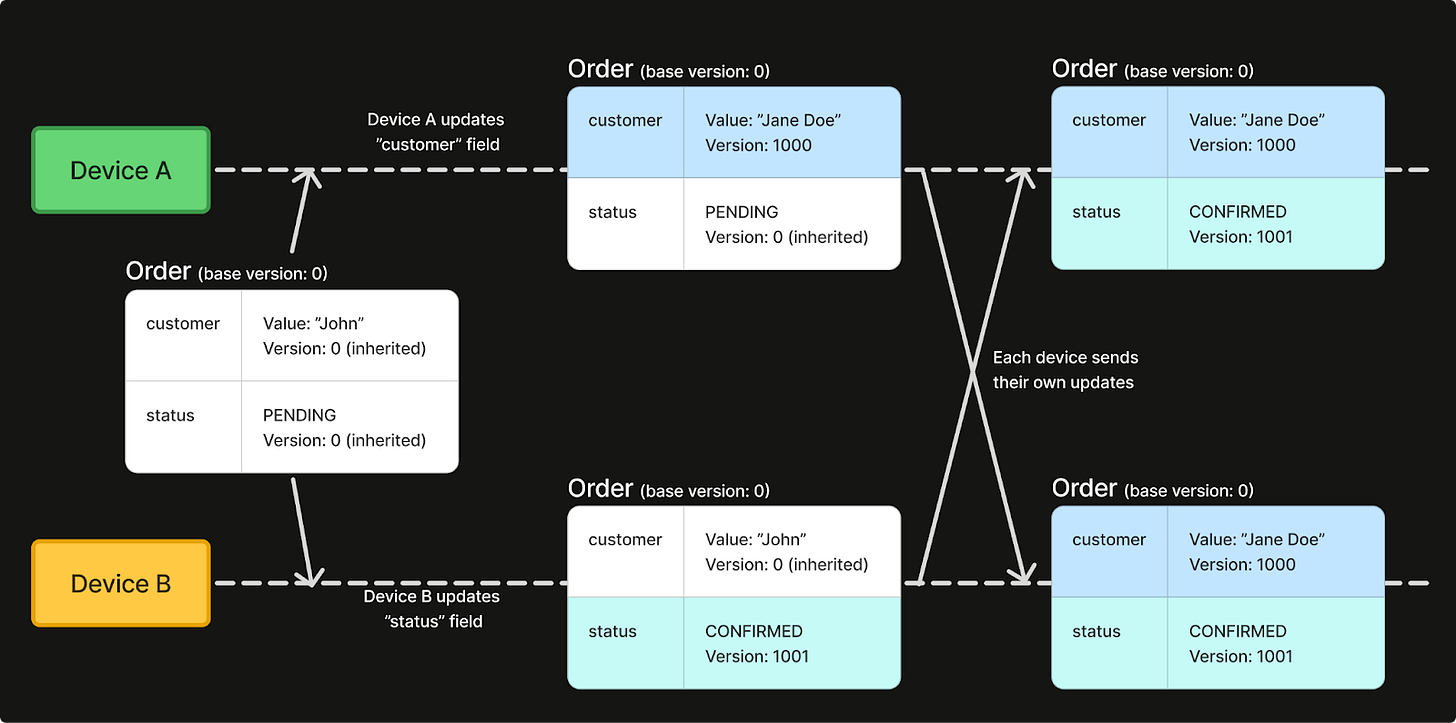

Assume we have two devices making concurrent modifications to different fields of the order protobuf. Device A updates the customer field, while device B updates the status field.

Both devices apply a local write to the order. When a device receives the other’s update a commutative merge is performed leveraging both version trees to reach a last-write-wins merge result.

// Device A: Update customer name

val orderA = existingOrder.copy(customer_name = "Jane Doe")

val deltaA = orderResolver.applyLocalWrite(/* ... */, timestamp = 1000)

// Device B: Update status (at the same time, different field)

val orderB = existingOrder.copy(status = OrderStatus.CONFIRMED)

val deltaB = orderResolver.applyLocalWrite(/* ... */, timestamp = 1001)

// When B receives A's update, both changes merge using the version trees

val merged = orderResolver.resolveIncoming(

deviceB.value,

deviceB.versionTree,

deviceA.value,

deviceA.versionTree

)

// Result: customer_name="Jane Doe", status=CONFIRMED

// Both updates preserved - no data lossScenario 2: Map Field with Concurrent Updates

Map fields require correct handling of deleted elements. Assume two devices update different keys in a map field, where one device also deletes a key.

// Device A: Add a metadata entry

val orderA = existingOrder.copy(

metadata = existingOrder.metadata + ("source" to "mobile_app")

)

// Device B: Add different entry and delete another

val orderB = existingOrder.copy(

metadata = (existingOrder.metadata - "old_key") + ("priority" to "high")

)

// After merge: all additions preserved, deletion applied

// metadata = { "source": "mobile_app", "priority": "high", ... }

// "old_key" removed (tombstoned)

val merged = orderResolver.resolveIncoming(/* ... */)Deleted entries persist in the version tree as tombstones allowing the resolvers to merge map changes correctly across devices. The crdt_tombstone_ttl option allows you to define a time-to-live (TTL) for tombstone entries to bound memory growth.

Scenario 3: Repeated Field with ID-Based Merge

Lists present a unique challenge during merge resolution given the sorting of elements could change across devices, even if the data is the same. Assume two devices modify different items in the order’s line items list.

// Existing order has items: [{ id: "item-1", quantity: 1 }, { id: "item-2", quantity: 2 }]

// Device A: Update quantity on item-1

val itemsA = existingOrder.items.map { item ->

if (item.id == "item-1") item.copy(quantity = 3) else item

}

val orderA = existingOrder.copy(items = itemsA)

// Device B: Update price on item-2

val itemsB = existingOrder.items.map { item ->

if (item.id == "item-2") item.copy(price_cents = 999) else item

}

val orderB = existingOrder.copy(items = itemsB)

// After merge: both item updates preserved

// items = [{ id: "item-1", quantity: 3 }, { id: "item-2", quantity: 2, price_cents: 999 }]

val merged = orderResolver.resolveIncoming(/* ... */)The crdt_id_field option tells the resolver which field identifies each element. Without it, the entire list would need to be replaced atomically (i.e. last-write-wins on the entire list).

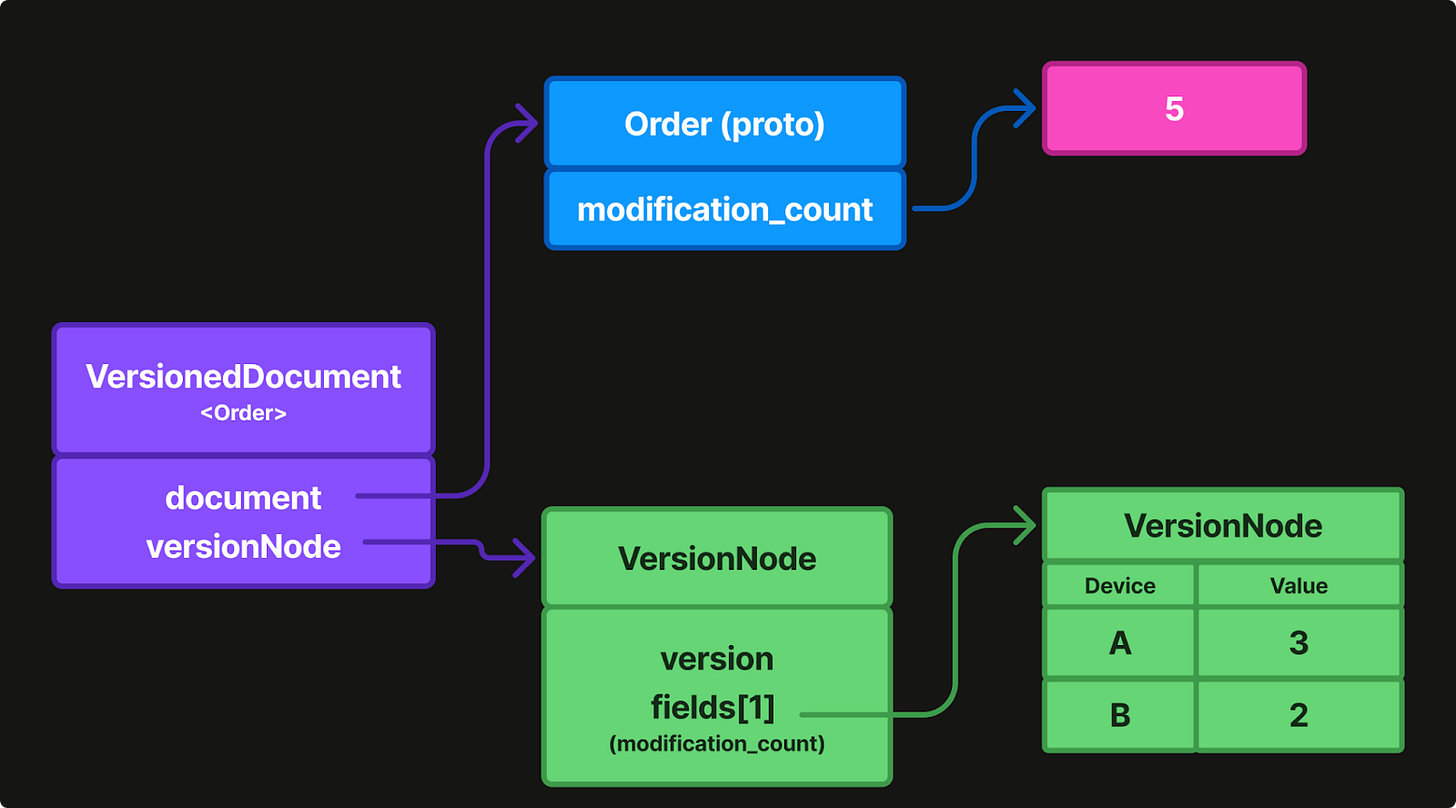

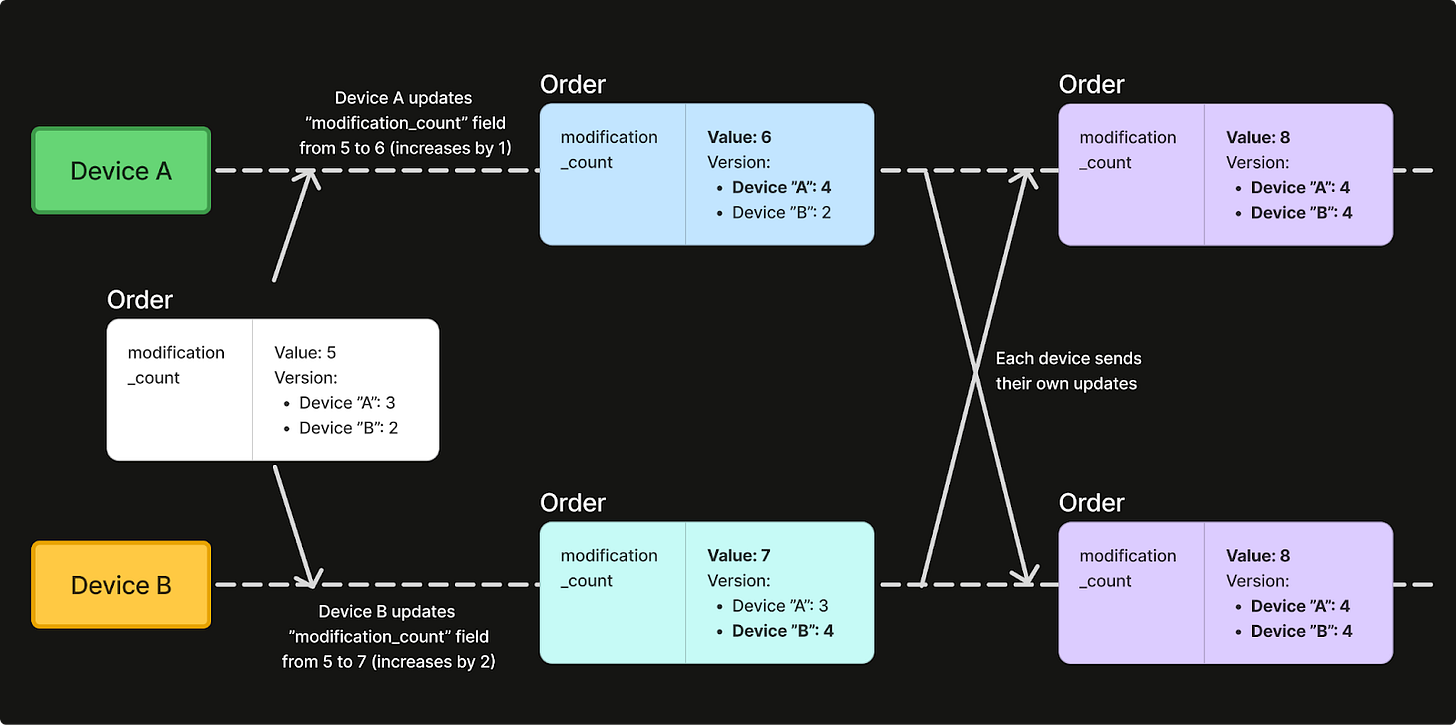

Scenario 4: Counter Field

When an integer or long field is marked with the COUNTER merging strategy, a G-Counter structure is stored in the version tree. Counter fields use per-actor tracking internally so that each device’s contribution is recorded separately. The counter value is the sum of all contributions, ensuring concurrent increments never lose updates, whereas a naive last-write-wins approach would lose all but one of them.

If two devices increment a counter concurrently, both increments are preserved.

// Both devices start with modification_count = 5

// Device A: Increment by 1

val orderA = existingOrder.copy(modification_count = 6) // 5 + 1

val deltaA = orderResolver.applyLocalWrite(/* ... */)

// Device B: Increment by 2

val orderB = existingOrder.copy(modification_count = 7) // 5 + 2

val deltaB = orderResolver.applyLocalWrite(/* ... */)

// After merge: modification_count = 8 (5 + 1 + 2)

// Counter tracks per-actor contributions and sums themScenario 5: Atomic Replacement vs Field Merge

Different fields might require different merge strategies. For example, you may want to REPLACE on updates to the receipt field, but MERGE on updates to the payment field.

// Device A updates payment method

val orderA = existingOrder.copy(

payment = existingOrder.payment.copy(method = "credit_card")

)

// Device B updates payment amount

val orderB = existingOrder.copy(

payment = existingOrder.payment.copy(amount_cents = 5000)

)

// After merge: both payment fields preserved

// payment = { method: "credit_card", amount_cents: 5000, ... }

// But for receipt (REPLACE strategy):

// Device A generates new receipt

val orderA = existingOrder.copy(

receipt = Receipt(pdf_data = newPdfA, generated_at = "10:00")

)

// Device B also generates receipt

val orderB = existingOrder.copy(

receipt = Receipt(pdf_data = newPdfB, generated_at = "10:01")

)

// After merge: Device B's receipt wins entirely (higher timestamp)

// No partial merge of receipt fields—it's atomicUse REPLACE for fields where partial merges don’t make sense: binary data, generated content, or tightly coupled field groups.

Results

Our approach is significantly more efficient and adds only minimal memory overhead to your existing data.

Why do we win? With a parallel version tree divorced from business data, we eliminate per-field CRDT container wrappers which lead to O(F x D) complexity during read and write operations. By only storing modified fields in our version tree, memory overhead plummets and we can achieve a massive reduction in DB operation latency.

But dropping the containers doesn’t come for free. You still need to support custom per-field merge strategies. We leaned into a schema-driven approach using protobuf options: MERGE for field-level resolution, REPLACE for atomic updates, COUNTER for commutative operations, and ID-based lists for element-level tracking.

Takeaways

Separating versions from data is less natural and requires additional information to be stored. Since the additional information was small in practice, our approach reduced CRDT memory usage by 4-5x when combined with various optimizations.

Our approach works for any application syncing structured protobuf data across distributed nodes. We use it in production and plan on scaling it to thousands of restaurants, allowing Otter POS customers to handle network partitions and concurrent updates seamlessly on low-end Android hardware.

If you know an even better approach, let us know.

I loved reading this. Thanks for publishing it. I have some observations, but overall this is exacly the kind of thing I've long been wanting to read more of: real world application of CRDT techniques.

First up I want to point out that this isn't really a direct like for like comparision. That doesn't mean it isn't a brilliant take on some of the ideas from https://josephg.com/blog/crdts-go-brrr/, and I love declartive merge policies (but what if policies conflict?!)

How is it not directly comparable? You have schema. You don't support structural removes/path edits. Nor do you have the same semantics as the Ditto map (add wins/remove wins structural with recorded type conflict?)

What really comes out of this for me is something I have been saying for years: CRDT _techniques_ are valuable, but implementation is *very* use case specific. The Ditto map has a great deal more flexibility but the cost of that is not zero. There are other ways I am sure Ditto could address performance too, "container CRDTs" are not per-se the problem. One method worth looking into further is decomposed CRDTs that match storage (see e.g. Bigsets)

Despite the non-comparable comparison, I think this is valuable work and I love to see actual industry posts on applying CRDTs in production.

I'd love to see a follow up about schema changes and maybe something about how you verified correctness.

The takeaway for me is don't pay for flexibility you don't need, which is often what you do if you use a general purpose solution to a problem in a specific domain. A solution tailor made for the domain will always win.